|

||||

| Posted May 2, 2003 | ||||

|

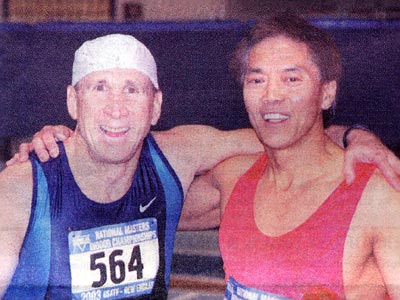

Stephen Robbins (at left in photo) and

longtime

friend and rival Harold Morioka dominated the M60 sprints at the 2003

Boston indoor masters nationals.

Dr. Robbins is considered the world's best-selling textbook author in the areas of management and organizational behavior.

|

Managing to excel at the sprints: Dr. Stephen Robbins of Seattle, Washington, is a textbook example of a sprinter pushing the envelope. Recently turned 60, this management expert and author is quietly intent on rewriting the record book. But thatís assuming heís healthy. A former business professor, Robbins has become a student of the bodyís limits. His injuries are almost as awesome as his dash marks, which include 11.34 for 100 at 52 and 22.98 for 200 at 53. His 51.63 for 400 at age 52 is yet another single-age world record.

He added another chapter to his

legend at the 2002 world masters championships in Brisbane, where

after a long absence from competition Robbins won the M55 100, 200 and added gold in the 400 relay. In

March 2003, he claimed national M60 titles in the indoor 60 and 200 in

Boston Ė winning the 2 by nearly 2 seconds. By Ken Stone Masterstrack.com: At age 58, you were among the oldest sprinters in the M55 field at the Brisbane WMA world meet, yet you won the 100 in 12.18 and the 200 in 24.76 as well as gold in the 400-meter relay. Even more amazing was that you did this coming off some devastating injuries. Could you describe in detail these injuries and how you rehabbed yourself to become a world champion again? Robbins: You havenít got enough space for me to detail all my injuries. (Not that Iím unique. All of us have to deal with it. I often joke that the best way to bond with someone you just met at a masters meet is to ask: ďSo, tell me about your injuries?Ē Theyíll go on for an hour!). Here are the lowlights on my injuries the past six years: May 1997: Injured my right Achilles. So I was out of shape for Durban. June 1998: Severe groin injury. Season over. Operation to repair in December 1998. February 1999: Another surgery. This time to repair torn meniscus in left knee. April 1999: Return of right Achillesí problem. Severe pain through Oct. 1999. August 2000: Tore left hamstring at nationals in 100m heat. January-June 2001: Achillesí continually sore. Unable to train much. August 2001: Kidney stone operation. The latest: At the 2003 indoor nationals in Boston, during the 200, I pulled something in my right shoulder just as I was entering the second turn. I had trouble pumping my right arm as I drove for home. Just when I think Iíve had every injury a sprinter can have, I come up with a new one. I went through a battery of tests May 1. I do have a torn rotator cuff. But they think I have about a 60 percent chance of being able to run in Puerto Rico. Theyíre putting me on a rehab program and I canít sprint for about 5-6 weeks. I wonít be in great shape for PR, but maybe I can at least be competitive. Iím hopeful. Re: rehab. I see a lot of specialists -- sports medicine, pain, physical therapists, chiropractors, acupuncturists, etc. I think regular massage is essential for managing injuries, so I get deep-tissue work done at least twice a week. Brisbane was a real surprise for me. I came in knowing I wasnít in shape. Because of lack of conditioning and my age, I just hoped to make the finals. Then on the morning of the first 100 heats, I started having this severe lower-back pain. I thought I threw out my back. I barely made it through the qualifying heats of the 1 and 2. By the finals, I felt OK. I later learned I had a kidney stone. When Bob Hayes died in September 2002, you must have felt a special sadness. He was the same age as you, and you competed against him in the mid-1960s. Can you recall your races with Hayes? What was your reaction to his death? I raced against Hayes only once or twice. I wasnít in his league. I was a good college sprinter but not outstanding. For instance, I never made it out of the heats at the NCAA. I did run all the time against Henry Carr. He was at ASU when I was at Arizona. But I never beat him. I knew that Hayes was seriously ill. Nevertheless, his passing hit me hard. I read about it while we were in Paris. That day, I thought about all his talent and how his life had turned out rather sadly. He never seemed to adjust to life after track/football. It made me realize how important it is to keep sport in perspective. Was Hayes the fastest sprinter you ever saw? What times would he been able to run on todayís tracks and in todayís shoes? Hayes had unbelievable leg turnover. His anchor leg on the 4x1 at Tokyo has to make you think there have been few to compare with him. I have long thought that Tommy Smith, in high gear, was as fast as Hayes. The difference was that Smithís style was deceiving. He didnít look like he was covering ground like Hayes did. In addition to tracks and shoes, donít forget about motivation (thereís real money in the sport now for elites), diet and coaching. I would guess that if Hayes had all these factors correctly aligned, he could have run in the 9.60s electronic. You were running sub-23 in the 200 as late as age 53. Do you consider the 200 your best masters event? Yes. My explosion out of the blocks isnít very good anymore. So my 100 suffers. I seem to be able to relax better in the 2. And I love running the turn. Tell me how you first became aware of masters track. Where did you first compete? At what age? I have my good-buddy Ed Oleata to blame for all of this. I was living in San Diego and Ed and I began working out together. He told me about masters track. I competed a bit in 1987, at age 44. But I didnít get serious until age 49. Back in 1993, you had just retired as a business professor at San Diego State University. Later you moved to the Seattle area. Did you move to accommodate your book-writing career or your masters track career? I moved for a change of lifestyle. I had been single for nearly 20 years; I was sick of meeting ďValleyĒ women; and I thought I needed a change in locale. I wanted to live in a more urban setting. Also, there were tax implications to the move. Washington has no state income taxes. You once told a newspaper: ďYou've got to be disciplined to be a writer. Iíve been up at 5 oíclock every morning, writing. Thatís every morning for 20 years. That discipline runs to track. Thatís not management, though. Thatís obsessive-compulsive behavior.Ē Are you still obsessed about training for track? I think I said that in about 1994. The answer today would be: No. I train diligently, but I have to admit Iím not as ďhungryĒ as I was in the mid-1990s. I had something to prove then. I had accomplished everything I had wanted in my professional life but not on the track. I got lucky in 1995. It was the first full season EVER that I went without injuries. I doubt that will ever happen again. You earned a doctorate from the University of Arizona and your books on business management, power and politics in organizations, as well as the development of effective interpersonal skills have become required reading in thousands of business schools around the world. What attracted you to this field? My undergraduate degree was in finance. And I have an MBA. It was only natural to study business for my Ph.D. But I have never been enamored with business per se. I was more interested in organizations (profit and nonprofit) and the psycho-sociological side of organizational life. So when I began writing, I wrote about what interested me -- organizational behavior, politics, power, interpersonal skills. I just finished a trade book on decision-making. It amazes me that people make so many consistent errors in judgment and decision-making. I think I can help people improve their decision-making skills. When I see something that interests me, and I think there might be a market for it, I start thinking about writing a book on it. Sick, eh? You also travel a lot to give seminars and talks. How do you combine training with these trips? I try to keep travel down to 3-4 day trips when Iím in serious training. I keep the long trips -- Europe, Asia, Latin America -- to years when there are no world championships. But Iíve been injured so often lately that it hasnít mattered. If Iím hobbling around at home, I might as well be hobbling around in New York or Paris (and the food will probably be better!). Do you consider yourself a retired college professor, or a full-time business writer and consultant? I consider myself a writer. Iíve been writing books since 1974. By the early 1990s, it had become a big business and I decided to give up the teaching so I could write full time. I liked teaching but I love writing. What occupies your ďday jobĒ time? When Iím home, my day is highly standardized. I research and write from about 6:30 am to 10:30 a.m. Monday through Friday. I have lunch at 11:30. I nap from about 12:30 until 2. I work out from 3-5. I still work out at around the same time that I did in high school and college. Iím not what youíd call a ďflexible guy!Ē Oh yeah, and I get a deep-tissue massage from 5 to 6 p.m. Mondays and Thursdays. What other hobbies or nonwork interests do you enjoy? My work is basically my hobby. I love writing and I canít think of anything Iíd rather be doing. Itís a great way to kill the mornings! I read quite a bit, but mostly on issues related to management and human behavior. We also travel a lot. Iím a living example of job specialization. I can basically only do two things well: write and run fast for a short distance. So Iíve stayed focused on those two activities. Youíve lived in Seattle for a while -- the same area that produced USATF Masters Chairmen Ken Weinbel and George Mathews. Have you ever thought about emulating them and getting involved in masters politics? Never! Iím not a politician. This even applies to my academic life. For instance, I have never sought office in my professional organizations. I never even ran for office in high school or college. Again, I think this reinforces my narrow focus. I want to race, not get involved in running politics. I want to write but not get sucked in to the politics of academia or publishing. Back to track: In spring 1993, not long after you turned 50, you ran a hand-timed 10.83 for the 100 in Santa Ana, California. Do you expect a similar outburst in 2003 in M60? I wish! Fast times come when you combine an absence of injuries, good training opportunities, lots of competitions and luck. Iím hopeful that 2003 will be a good year for me. But I hoped for that in 1998, when I turned 55, and I was laid up most of that year. It typically takes about three years or so to get into top condition after long layoffs. I began training hard in 1992 but didnít peak until 1995 or 1996. I consider 1997 through 2000 as a layoff period because I couldnít maintain follow-through. Iíve now had two years where -- while Iíve had some injuries Ė Iíve still been able to get in a few meets. If I can stay healthy through August (a big if), and additionally get the mental toughness to do the workouts necessary for my base, I think I can run well in 2003. Are you pointing for any specific times this year -- or just titles in Puerto Rico or Eugene? What events will you enter? Iíd be lying if I didnít tell you that I had specific goals. I always have goals! In 2003, Iíd like to run 11.85. Ron Taylorís 11.70 WR is out of my league. I think Iím capable of sub-24 in the 200, but I would need some breaks. I hate the 4. I hate the training and I hate the race itself. But itís a challenge. Iím fortunate to have God-given speed. That carries me in the 1 and 2. The 4 requires cardio-capacity. Iíve signed-up for the 4 in Puerto Rico. If I can get into shape, Iíll run it. My goal in 2003 is to make the M60 records just a bit tougher so itíll take Bill Collins more than one meet to smash them when he turns 60. Whoís your biggest rival on the track? Harold Morioka? Courtland Gray? Harold is always a factor. Weíre only two days apart in age, so I guess weíre permanently linked ďuntil death do us part.Ē Depending on the year, other major competitors would include Courtland, Stan Whitley, Paul Edens, Joe Johnson, Roger Pierce, Ed Roberts, Stan Wald (of South Africa), Peter Crombie (of Australia) and Kozabu Kaihara (Japan). I should add that I really donít focus on rivals. It took me 35 years to learn this: I have no control over my competitors. I can only control elements of my performance. The reality is that if some M60 guy comes out this year and runs 11.50, Iím gonna get beat. If Iím healthy and in shape, and the best guy runs 12.40, I can win. I donít understand why we spend so much time focusing on who is in a race and how fast they can run. Itís irrelevant because we canít control what other people do. You often wear a cap while racing. What is this -- a bicyclist cap turned backward? How did this start? Is this a superstition, or are you vain about hair loss? Theyíre paintersí caps. I wear them because my dermatologist told me not to let the sun hit my head. I wear them in workouts, too. Iím prone to nonmalignant melanoma, so I cover up. At indoor meets, I guess itís superstition. Youíve had serious injuries at various points of your masters career -- halting some record attempts in various age groups. What times would you have been capable of had you not been hobbled at various points? I really canít guess. The fact is that no fast guy gets the luxury of having an injury-free career. Injuries come with the territory. How fast would Collins or Whitley have run if they didnít get hurt? Joe Johnson from New Jersey has incredible leg turnover, but he gets hurt a lot. I canít think of any top-10 sprinter over 50 -- who has been competing for more than a few years -- who hasn't had to deal with the injury problem. In masters sprints, the bottom line is not who is the fastest. Itís who is the fastest among those who are able to compete. What we could have done doesnít count. Have doctors ever advised you to give up track? Yes, in 1996 and again in 2001. I have arthritis in my hips and my Achilles problem is chronic. I tell them: ďIíll listen to my body,Ē then I go out and do what I want. I enjoy working out. It allows me to eat poorly and not gain weight. I donít want to give up competition. But I also donít want to be in a wheelchair at 70. So if or when it looks like my aches and pains are going to undermine my lifestyle, Iíll quit. Erwin Jaskulski of Hawaii recently ran world records of 36.49 for 100 and 1:27.85 for 200 in the M100 age group. Yet according to the WMA Age-Graded Tables, those records are relatively soft. What do you think of EJís marks -- and what will you be running at his age? Woody Allen said: ď90 percent of success is just showing up.Ē Iíd love to be able to show up at the 2043 nationals! Seriously, if my body holds up, Iíd like to compete into my 80s. But Iíve noticed an interesting phenomenon: Records seem soft from a distance. When you get to that age, suddenly theyíre not so soft anymore. When I was 50, the M55 records looked easy. When I was 55, the M60 records looked easy. As you close in on those ages, you come to respect them a great deal more. I guess Iíd say: Over 80, there are no soft records. Any guy over 80 who can still finish a 100 or 200 is one tough dude. | |||

|

|